The author writes about his exhibition as follows:

‘The artist, whose work balances between the real and the imagined, will present paintings from two original series: ’From the Borderland of Reality and Dreams‘ and ’Visions”. His works are full of symbols, intense colours and emotions, and their rich painterly form, full of contrasts and chiaroscuro, encourages individual interpretation. The canvases feature both unusual landscapes and evocative scenes with mysterious characters – from those that arouse anxiety to those full of light and harmony.

In his art, Ruppental draws inspiration from impressionism, surrealism and keen observation of nature. These are what create the unique atmosphere of his paintings, which attracts viewers from all over the world. The artist is associated with the Macabre Gallery and the Dark Art Movement. His works have been exhibited at the BBA Gallery in Berlin and were among the finalists for the European Artist Award 2024 in Florence. He has won numerous awards and distinctions in prestigious competitions such as the World Art Awards, American Art Awards and Art Collectors Choice Awards.

The exhibition will be on display until 31 August 2025 in the lobby of the Rzeczna Art Gallery.

The Rzeczna Art Gallery is architecturally accessible and pet-friendly.

Translated with DeepL.com (free version)

Italy draws people in with its history, art, and landscapes. But for me, just as fascinating are its people – expressive, genuine, and kind.

It is they – in their everyday roles – who create the atmosphere of the places where I pause with my camera.

A loud vendor at a Sicilian market, a pensive mother with her daughters in a Lombard village, an elegant jeweler on Florence’s Ponte Vecchio – each of these individuals had something about them worth remembering.

The portraits presented here were taken across various corners of Italy. What unites them is authenticity – each captured in natural, unposed moments, without interference from the photographer. Chance encounters, fleeting glances, gestures that lasted only a second.

It’s a visual sketch of everyday life – a record of the unexpected, the warm, and the surprisingly beautiful in ordinary faces and moments. A close-up of another human being. No embellishments. No agenda.

Tomasz Karnowka

About the Author

Tomasz Karnowka – a native of Silesia and resident of Rybnik, graduate of the Silesian University of Technology, and retired mining professional. A photography enthusiast, he has been an active member of the “Indygo” Photographic Group in Rybnik for many years, and later of the “Fotobalans” Photographers’ Association in Wodzisław Śląski. He co-organizes photographic events, has won awards in photography competitions, and has participated in numerous group exhibitions.

He is the author of two solo exhibitions, presented among others during the Rybnik Photography Festival:

– In the Lighthouse’s Light (2020) – a portrait series of individuals with intellectual disabilities

– Nieboczowy – The Disappearing Village (2018, co-author: B. Rochalski) – a documentary series capturing the transformation of a village affected by the construction of the Racibórz Dolny reservoir

Italy has long been his favorite travel destination – he is captivated by its nature, landscapes, architecture, and history. Just as important to him are the people he meets there: their everyday lives and spontaneous encounters become a rich source of photographic inspiration.

This exhibition is the result of that deep and multifaceted fascination.

Information from the author

The photographs were taken during my travels in Italy and are mostly in the vein of street photography, based on authenticity and respect for the other person.

Most of the photographs were taken with the permission of the subjects or in situations where the presence of the camera was visible and not objectionable.

Some frames were taken on the move or from a distance, without the possibility of prior consent – none of them, however, depict people in a way that violates their dignity.

If in doubt, people who recognise themselves in the photographs are asked to contact the author.

The author bears full responsibility for the photographs presented.

The organiser of the exhibition is not responsible for any image claims.

Contact the author:

tomaszkarnowka.fotografia@gmail.com

The exhibition is non-ticketed and can be viewed in the Gallery lobby.

Gallery

Presentation of Polish contemporary sculpture from the collection from the Centre of Polish Sculpture in Orońsko

The exhibition is based on a selection of works related to broadly understood figuration. This is a subject characterized by a certain timelessness. Figuration is understood as an inexhaustible source of inspiration, the end of which is difficult to predict, which is confirmed in artistic practice. Even in the rhythm of the succession of generations, it is subject to extreme transformations that can be reduced to a common denominator and derived from a single genetic prototype. The consistent development of this narrative is one of the important structural axes of the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Sculpture of the CRP in Orońsko.

The Centre of Polish Sculpture has been building a representative collection of Polish sculpture for over forty years, with particular emphasis on works created in the second part of the 20th century and today. The establishment of this institution is associated with the activities of creative workshops and an outdoor exhibition of artists’ works in 1965, and then the opening of the Centre for Creative Work of Sculptors, so that in 1981 the Centre of Polish Sculpture began to function as a state institution subordinate to the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage. Currently, the collection, consisting of sculptures, objects and installations of over two thousands works, and is supplemented by almost five hundred deposits. Most of the works come from the post – war period, although the collection also includes those from the beginning of the 20th century, such as the works of Konstatnty Laszczka and Stanisław Ostrowski. As well as from the interwar period e.g. Katarzyna Kobro, Olga Niewska, Xawery Dunikowski and August Zamoyski. An important part of the collection are works that make up the latest chapter in the history of Polish sculpture, and especially those created in the recent years. This applies primarily to the works of the young generation, which – as part of the Youth Triennial organized by the Center – has the opportunity to make its artistic debut. The Orońsko Sculpture Park presents works by world – famous artist, such as: Magdalena Abakanowicz, Ursula von Rydingsvard, Wojciech Fangor, Anthony Cragg and Adolf Ryszka. The works collected for over four decades are used by the Centre and other museums and galleries to implement exhibitions projects in Poland and abroad.

The curatorial text was written by Dr Jarosław Pajek

The exhibition at the Rzeczna Art Gallery presents works by outstanding Polish artists, listed in alphabetical order:

Agata Agatowska

Andrzej Bednarczyk

Bronisław Chromy

Jan Cykowski

Xawery Dunikowski

Barbara Falender

Jerzy Grygorczuk

Władysław Hasior

Krystyn Jarnuszkiewicz

Józef Kaliszan

Mieczysław Kałużny

Alfons Karny

Jan Kucz

Stanisław Kulon

Konstanty Laszczka

Tadeusz Łodziana

Jerzy Mizera

Adam Myjak

Sławoj Ostrowski

Antoni Janusz Pastwa

Andrzej Pawłowski

Maria Pinińska-Bereś

Adam Procki

Antoni Rząsa

Stanisław Słonina

Wanda Sokołowska-Majerska

Ludmiła Stehnova

Wacław Szymanowski

Janusz Tkaczuk

Jacek Waltoś

Jan Stanisław Wojciechowski

Antonina Wysocka-Jonczak

August Zamoyski

Barbara Zbrożyna

Kazimierz Gustaw Zemła

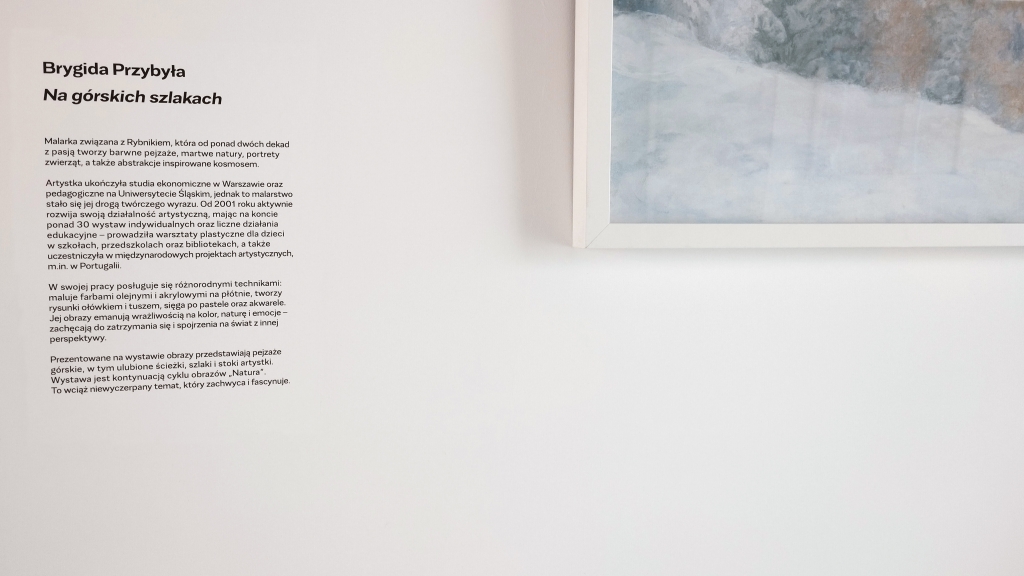

A painter associated with Rybnik, who for over two decades has passionately created colorful landscapes, still lifes, animal portraits, as well as cosmic-inspired abstractions.

The artist holds a degree in economics from Warsaw and completed pedagogical studies at the University of Silesia. However, painting became her true path of creative expression. Since 2001, she has been actively developing her artistic practice, with more than 30 solo exhibitions to her name, as well as numerous educational activities – she has conducted art workshops for children in schools, kindergartens, and libraries, and has also taken part in international art projects, including in Portugal.

In her work, she uses a variety of techniques: painting with oil and acrylic on canvas, drawing with pencil and ink, and working with pastels and watercolors. Her paintings radiate a sensitivity to color, nature, and emotion – inviting viewers to pause and see the world from a different perspective.

The paintings presented in this exhibition depict mountain landscapes, including the artist’s favorite paths, trails, and slopes. The exhibition continues the “Nature” series – an ever-inspiring theme that never ceases to fascinate and delight.

Gallery

About the project:

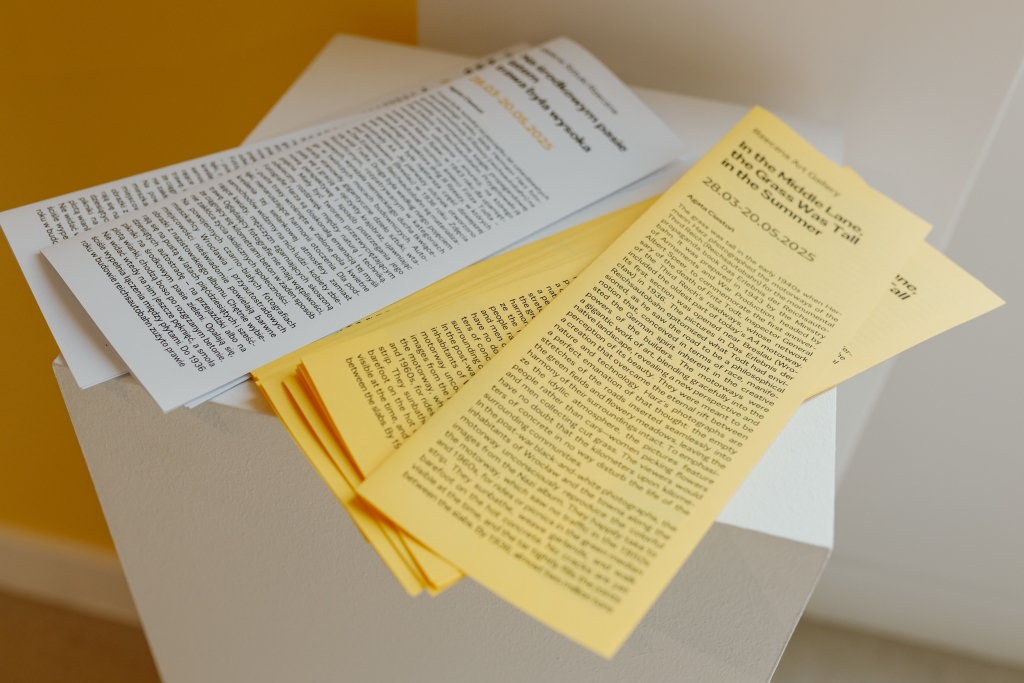

In the exhibition, the highway – a road with strictly defined parameters, with precisely calculated angles of turns – is a labyrinth. It becomes a portal transporting to the convoluted past: to the scorching summer in Lower Silesia in the late fifties, an exceptionally cold winter of 1945, the Third Reich, the Polish People’s Republic, moments of geopolitical change, far-away events, and the people whom it connected. What does the cracked highway concrete remember, which in the exhibition is both a metaphor and a genuine object? How quickly does the grass grow, and do the same butterfly species as seventy years ago fly over the highway now? The exhibition takes us on a journey, which is the destination in itself.

About the author:

Agata Ciastoń – an independent curator, researcher, and author, doctor of cultural studies. For years, she has been working with cultural institutions, educational establishments, and publishers. She came up with, coordinated, and curated collective exhibitions, including “Poetry and performance. The Eastern European perspective” and “ »Photography« Monthly 1953-1974”, as well as many solo exhibitions. She also fulfilled the role of curator during international art residencies. In her work, she is mostly interested in the broad topic of borders and territories. In her projects, the themes of polysemy of the landscape and humanity in relation to the world of animals, plants, and objects appear recurrently. In the summer of 2024, her book, “In the Middle Lane, the Grass Was Tall in the Summer”, was published with Wydawnictwo Warstwy.

Gallery

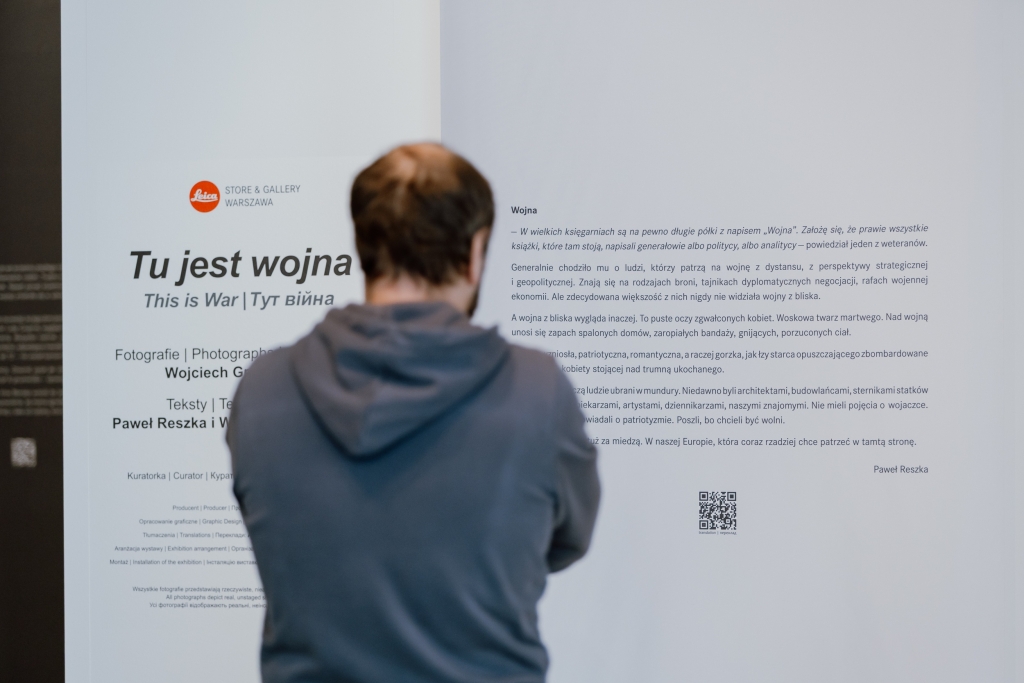

About the project:

Photography exhibition “This is War” by Wojciech Grzędziński is a moving documentary of the conflict in Ukraine, from the moment of the Revolution of Dignity in 2013, to today’s events connected with Russia’s full-scale invasion of 24th of February, 2022. Grzędziński, an exceptional Polish photojournalist, documents not only tragic events at the front, but also the everyday lives of ordinary people affected by the war. His photos, both the well-known and award-winning at the Grand Press Photo competition, and the ones displayed for the first time, tell stories through the lens of individual lives and tragedies that stay in memory for a long time. Grzędziński’s photos are accompanied by texts by Paweł Reszka, an acclaimed journalist and war correspondent.

Together they create a story about everyday life in times of war – both at the front, and in faraway places, where war also changes lives. The exhibition isn’t limited to only photographs – it also contains movies, slideshows, and artifacts, which widen the context and allow for a better understanding of the war. An integral part of the exhibit are extensive descriptions, comments, and articles in the form of material sheets hanging from the ceiling. All texts have been translated into English and Ukrainian, which makes the exhibition more accessible to the international audience.

Attention! War directly affects life and health. Exhibit “This is War” displays authentic texts and images from the war in Ukraine. You may not be prepared for this. Underage people may visit the exhibit under parental supervision.

About the authors:

Wojciech Grzędziński – photojournalist. Born in 1980 in Warsaw. Prize-winner of many photography competitions: World Press Photo, Visa D’Or, NAPA, Sony World Photography Awards, Grand Press Photo, and others. Author of the Photo of 2009 and Photo of the Decade (2014) in the BZWBK Press Photo competition. Juror of Polish competitions, both national and local. In his photography, he is interested in humanity and emotions. He repeatedly photographed in war zones and immortalized the consequences of armed conflict. In 2011-2015, he supervised the team of photographers in the Chancellery of the President of the Republic of Poland and was the personal photographer to the President of the Republic of Poland. Stipendist to the Minister of Culture and National Heritage for 2014 and 2018. A member of the Union of Polish Photography Artists (ZPAF) and Press Club Polska. Since February 2022, he has documented the war in Ukraine.

Paweł Reszka – journalist, war correspondent (among others in Georgia and Ukraine), best-selling books author. He collaborated with “Rzeczpospolita” as a correspondent in Moscow. He was the leader of the investigation department for “Dziennik”. He wrote for “Newsweek Poland” and “Tygodnik Powszechny”. Since 2019, he’s been a journalist for “Polityka” weekly. His most well-known books are “Mali Bogowie”, “Chciwość. Jak nas oszukują wielkie firmy”, and “Czarni”, among others. He is a two-time winner of the prestigious Radio ZET award named after Andrzej Woyciechowski.

Curator of the exhibition: Monika Szewczyk-Witek

The Producer and Partner of the exhibition is Leica Store & Gallery Warszawa